High U.S. Dependence on Organic Imports and the Need for Organic Integrity Awareness

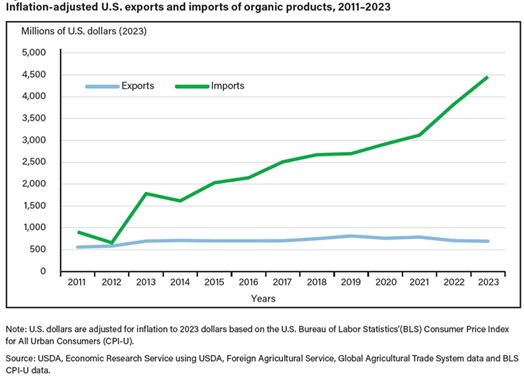

The Organic Outlook session at the 101st USDA Agriculture Outlook Forum, on February 28, 2025, highlighted an important trend for the $69.7 billion dollar U.S. organic market: organic imports far outpace domestic production. For example, in 2021, organic retail sales were estimated at more than $52 billion, of which U.S. farms and ranches sold nearly $11 billion (Raszap Skorbiansky, 2025a).

Organic product imports also outpaced exports, with a slightly positive domestic upturn for organic commodities like soy. Competition from lower cost imported organic products is one of the key barriers to organic production increase in the U.S. Imported organic products are also the highest risk area for organic integrity.

Fraudulently labeled organic products garner premium pricing without the added costs of production borne by certified organic producers. Organic integrity issues hurt both buyers of falsely labeled organic products and the livelihoods of certified organic producers. Even as the Strengthening Organic Standards (SOE) regulatory update has improved record-keeping and integrity checks in supply chains, gaps remain in prevention and enforcement for organic fraud. From farm to consumer, importer to retailer, there are actions we can all take to close the “fraud gap.”

The Growing Import-Export Imbalance

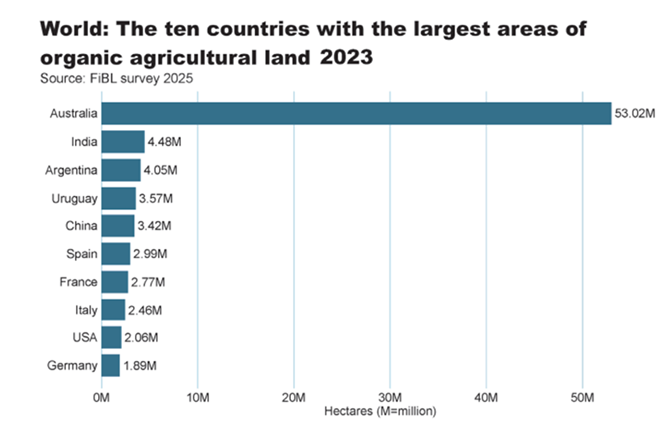

Despite consumer interest in organic products, domestic acreage devoted to organic commodities declined 10.9% between 2019 and 2021 and dropped an added 6.8 percent by 2024. In contrast, non-U.S. global acreage for organic and transitioning to organic increased 543% between 2000 and 2022 (Raszap Skorbiansky, 2025b). There is a stark contrast between the percentage of organic production in the U.S. compared to other countries.

According to the 2022 U.S. Census of Agriculture, organic farming systems were used on less than 1 percent of U.S. cropland and less than 1 percent of pasture and rangeland. The European Commission set a target of 25 percent organic land in the EU by 2030. On average, countries in the EU have about 20 percent organic acreage (Raszap Skorbiansky, 2025b).

Global organic acreage by country

Source: FiBL, 2025.

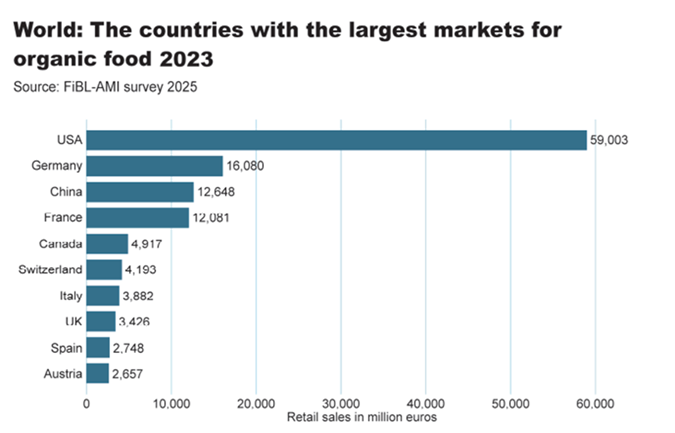

Even as the U.S. is among countries with the least acreage allocated to organic production, this country is the world’s largest market for organic products.

Source: FiBL, 2025.

The largest recent increases in organic acreage include higher fraud risk areas of India and Asia (Roseboro, 2023). These areas, in addition to organic soy imports from Argentina, were highlighted as key risks in the 2025 USDA Organic Outlook session. In 2021, the NOP ended its organic recognition program with India due to concerns over organic integrity of imported products (Roseboro, 2023).

Strengthening Organic Enforcement

U.S. producers are calling for increased scrutiny of imported organic products such as more testing of product at ports of entry (Hawkins, 2024). These requests are in addition to the National Organic Program (NOP) SOE rules that have been in place for one year now. SOE rules include stronger documentation requirements for organic import certificates, including use of the Organic Integrity Database (OID) to generate mandatory electronic import certificates (NOPICs). In addition, by expanding the number of organic-specific Harmonized System (HS) codes, the SOE efforts made it easier to track the volume, value, and origin of organic imports.

SOE rules also require more of the supply chain to be certified, including brokers and handlers. The requirements led to an increase in certification applications in 2024. Scott Rice, Senior Director, Regulatory Affairs, at the Organic Trade Association, cited 2,991 new certification applications in the U.S., and 6,217 globally (USDA Organic Outlook, 2025). The demand put a strain on certification bodies, which were already stretched for capacity.

While the SOE rules have increased transparency on organic integrity of imports, the NOP has limited enforcement authority outside of the U.S. (Roseboro, 2024). The NOP must also manage hundreds of complaints annually, for both domestic and international products. To be successful, the NOP needs to be able to focus its limited resources on halting fraud with large-scale market impact over addressing marketing misstatements by a small brand. From farmers to consumers, importers to retailers, we all have a role to play in ensuring organic integrity and reducing marketing errors and the volume of smaller violations.

Certified Operations

SOE requires every certified operation to have a fraud prevention plan. These plans identify areas of risk and steps to mitigate potential fraud. Just having a plan may meet certification requirements, but the plan will not prevent integrity issues unless there is ongoing review, auditing, and implementation. This can be a burden for small- to mid-size operations without internal resources. Outsourcing these services to an experienced team can be a cost-effective approach.

As a certified entity, your messaging to consumers can build an understanding of organic integrity. According to the Organic Trade Association, many consumers are not aware of the full range of “free from” attributes associated with certified organic products (OTA and Eurofins, 2025). Transparent communication on what organic is (and is not) can go a long way toward educating consumers.

Retailers

Retailers that do not process organic products and retail locations that process organic products at the location of final sale are not required to be certified. However, retailers are key market access points for organic products. Responsible retailers ensure the products that they sell are certified. This line of defense may be less effective, however, for online retailers and mid-market retailers that lack processes to ensure the organic products they sell are certified. Unrestricted markets are a common pathway for fraudulently labeled products to be sold to consumers. These markets include shopping sites where organic products are offered by third parties, without any requiring proof of certification prior to being offered for sale.

Bolstering retailer engagement through product audits, compliance reviews, and requiring upfront proof of organic certification for products marketed and labeled organic would protect consumers.

Co-Packers

When products are produced by a co-packer, or under a private label agreement, the brand or company marketing the product may not be certified even if the product is certified organic. Unfortunately, it is not always possible to identify certified organic products produced by co-packers in the Organic Integrity Database (OID). Closing this transparency gap would help reduce the number of organic integrity complaints due to products “not being in the OID.”

Brands that are not certified, but market products packed by a certified co-packer, should avoid implying that the brand itself is certified organic. Conducting a compliance audit and educating your marketing team on these issues could help reduce the risk of complaints.

Consumers

Consumers are most at risk from misleading organic claims. With limited exceptions, such as operations that make less than $5,000 in gross annual organic sales, foods that make organic claims must be certified. Consumers should check that labels including organic claims also include a “Certified organic by” statement on the product information panel. Consumers can check the certification for many products using the OID search and submit a complaint to the NOP if necessary. Another action to consider would be reporting product concerns to the retailer.

Conclusion

The U.S. market has high demand for organic products and reliance on imports to meet the demand. The situation offers both an opportunity for growth of domestic organic production and risks from fraudulent imported organic products. Protecting organic integrity helps level the playing field for organic production. This is an important function of the NOP. However, all participants in the organic supply chain and consumers can foster a fair and thriving organic market by supporting organic integrity.

References

Hawkins, L. (2024, July 10). July 2024 Policy Update. Organic Farmers Association. https://organicfarmersassociation.org/news/july-2024-policy-update/

Organic Trade Association and Eurofins. (2025). Consumer Perception of USDA Organic and Competing Label Claims Report | OTA. https://ota.com/about-ota/press-releases/younger-health-conscious-consumers-are-embracing-organic-ota-survey-shows

Research Institute of Organic Agriculture FiBL. (2025). organic-world.net – 2025 edition of “The World of Organic Agriculture.” https://www.organic-world.net/yearbook/yearbook-2025.html

Raszap Skorbiansky, S. (2025a). Organic Agriculture | Economic Research Service. https://www.ers.usda.gov/topics/natural-resources-environment/organic-agriculture

Raszap Skorbiansky, S. (2025b). Organic situation report, 2025 edition. (Report No. EIB-281). U.S. Department of Agriculture, Economic Research Service. https://ers.usda.gov/sites/default/files/_laserfiche/publications/110884/EIB-281.pdf?v=48642

Roseboro, Ken. (2023, September 7). Fraud is “unquestionably, the biggest threat to organic.” The Organic & Non-GMO Report. https://non-gmoreport.com/articles/fraud-is-unquestionably-the-biggest-threat-to-organic/

Roseboro, Ken. (2024, November 18). USDA warns certifiers about fraudulent organic soybeans and soymeal from West Africa. The Organic & Non-GMO Report. https://non-gmoreport.com/articles/usda-warns-certifiers-about-fraudulent-organic-soybeans-and-soymeal-from-west-africa/

USDA Outlook Forum 2025 Organic Outlook (2025). (Registration Required) https://www.usda.gov/about-usda/general-information/staff-offices/office-chief-economist/agricultural-outlook-forum